Fashion Development

In hardly any other time has fashion changed as quickly as in the period between the two world wars. From the feminine and overloaded fashion of the Belle Époque, to the sporty, androgynous silhouette of the 1920s, to the ladylike and elegant fashion of the early 1930s, fashion underwent a dramatic change of 360 degrees between 1914 and 1933.

Fashion in Social and Historical Context

Dinner dress (left) of velvet and seamed chiffon with a garnish of silver lace. Next to it a princess dress with soutache embroidery — Illustrierte Frauen-Zeitung, no. 21 (36), November 1st, 1908.

Dinner dress (left) of velvet and seamed chiffon with a garnish of silver lace. Next to it a princess dress with soutache embroidery — Illustrierte Frauen-Zeitung, no. 21 (36), November 1st, 1908.

Summer dress in the fashionable silhouette of 1913 — Elegante Welt no. 18, April 30th, 1913. Photo: Atelier Ernst Schneider, Berlin, Germany

Summer dress in the fashionable silhouette of 1913 — Elegante Welt no. 18, April 30th, 1913. Photo: Atelier Ernst Schneider, Berlin, Germany

Those who believe that fashion is a negligible part of historical development fail to recognise the fact that clothing fashion is a reflection of society and its changes. Fashion is a reflection of the spirit of the times, social conventions, the ideals of an era and the social position of a person within society. In addition, fashion is also an expression of personal taste and a desired or unwanted statement of the wearer. People also show their affiliation to a certain group by wearing a uniform style of clothing, regardless of whether this group is defined by gender, age, political or religious beliefs, ethnic origin or similar. If you don't want to be outside a social group, you have to go with the fashion. Following fashion and its trends is therefore an indispensable social necessity in modern society.

The driving force behind the constant change in fashion is, in addition to the spirit of the times, the human desire for change and the irresistible appeal of anything new. No fashion is permanent, only the change in fashion is constant. This is how fashion editor Ola Alsens' statement proves to be true:

"After a certain time, every style of taste will outlive itself. [...] Everything that is frequently seen and familiar becomes boring and loses interest."1

The times when clothing served as mere protection against wind and weather are long gone. Whereas in the Middle Ages noble cloth and coloured fabrics were reserved for kings, nobles and particularly wealthy merchants, since the French Revolution in 1789 and the rise of the bourgeoisie in the 19th century clothing has become a visible sign of social and economic status for ever broader classes. Decisive for this were the developments of the steam engine, the spinning machine and the mechanical loom at the end of the 18th century, which gave the initial spark to the Industrial Revolution. Enormous increases in production and greater efficiency in production led to drastically falling prices for yarns and fabrics. The invention and rapid spread of the sewing machine in the 1850s did the rest to make clothing affordable for the broad masses of the population.

At the same time the first large department stores were founded in major European cities. New methods and sales strategies were developed with the aim of increasing turnover, which should attract customers. Department stores introduced ready-to-wear fashion in standard sizes, so that clothes could be offered at lower prices. This made it possible to buy off the rack, which was much cheaper than tailoring the clothes. In order to offer the customers always something new and to attract them to the department stores, seasonal fashion was introduced. Magnificent product presentations in shop windows and showcases were intended to entice customers to buy. Thus fashion developed at the end of the 19th century into the driving force of industry and the consumer society that was forming.

On the Threshold of the 20th Century

Women's fashion 1912. From left to right: capricious spring dress in glazed taffeta, tea dress with Russian embroidery, and a dress in cheviot with white and gray striped fabric with asymmetrical jacket — Elegante Welt, no. 13, 24 & 9, 1912. Photos: Studio Henri Manuel, Paris (left); Studio Ernst Schneider, Berlin.

Women's fashion 1912. From left to right: capricious spring dress in glazed taffeta, tea dress with Russian embroidery, and a dress in cheviot with white and gray striped fabric with asymmetrical jacket — Elegante Welt, no. 13, 24 & 9, 1912. Photos: Studio Henri Manuel, Paris (left); Studio Ernst Schneider, Berlin.

In order to understand the radical changes in fashion in the period between the two world wars, it is essential to take a closer look at the development of fashion and society up to 1914 and thus to see it in context.

The Society of the Belle Époque

In Europe, the period of the Belle Époque was a puritanical era, with strict moral values and fixed ideas about the roles of the sexes. The industrialisation of the 19th century separated gainful employment from the household. The private space of the household became a purely female domain, while the public space became the sphere of male-dominated gainful employment. According to Erica Carter, this gender-specific separation of spaces became the social norm and one of the "fundamental dichotomies of bourgeois modernity."2 While "productive work" was now connoted as male, women were assigned "reproductive work", which was to be limited to bringing up children and running the household.

Female existence was also that of the faithful and unquestioning companion of her husband, whereby she was granted only very limited rights, especially as a wife. Society expected her to fit in with the role of wife and mother that was intended for her. It was difficult to lead a different life outside of this understanding of roles. However, as early as the mid-19th century, and increasingly since the turn of the century, women reformers had begun to organize themselves in political associations in the United States and Europe to demand their right to more independence from men, better educational opportunities, and political participation. So women were only from 1895 in the German Empire allowed to take the Abitur and from 1908 to study.3

Paris the Centre of Fashion

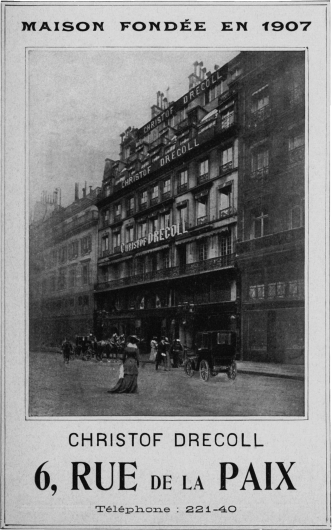

Advertisement of the Parisian fashion house Christof Drecoll on Rue de la Paix — Les Modes no. 76, April 1907

Advertisement of the Parisian fashion house Christof Drecoll on Rue de la Paix — Les Modes no. 76, April 1907

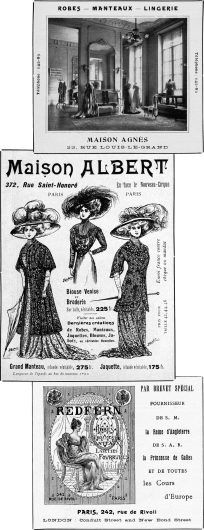

Ads by Paris couturiers Agnès, Albert and Redfern — Les Modes no. 98, February 1909

Ads by Paris couturiers Agnès, Albert and Redfern — Les Modes no. 98, February 1909

The undisputed centre of the fashion world around 1900 was the French metropolis of Paris, which at that time was one of the largest cities in the world and also the cultural centre of Europe. Paris had held this status as an unconstrained fashion metropolis since the times of King Louis XIV, whose style and representation became the model for all European courts. Despite the revolution of 1789, Paris was able to maintain and even expand this position in the 19th century.

At the beginning of the 20th century a few leading fashion houses had established themselves. Callot Soeurs, Doucet, Christof Drécoll, Charles Frederick Worth and Jeanne Paquin were the most important of these4, whose latest creations were not so much shown at fashion shows but mainly at the great horse races in the Parisian region, such as the horse racecourses of Longchamp or Auteuil, by well-to-do ladies of society. The Sunday horse races were the social event to which tens of thousands of French people from all walks of life flocked, and in addition to the races, the latest fashions of high society in Paris were shown. The ready-made departments of the department stores sent their tailors to the horse races in order to re-cut the clothes seen there as quickly as possible, so that they could offer their customers the latest fashion without much delay. Usually the copied models could be purchased the very next day.

What Paris meant to the elegant lady, London meant to the distinguished and sophisticated gentleman. From the capital of the worldwide British colonial empire came the new menswear, which was considered the standard for the well-dressed gentleman all over the world. Especially around London's Bond Street the most respected menswear designers of the Empire were grouped. But there were also influential ladies' fashion houses in Great Britain. John Redfern founded a fashion house in 1881 that had branches in Paris and New York.5 The horse races here, just like in France, were regarded as social highlights where the latest fashions were launched. Especially the famous Royal Ascot Racecourse was a meeting place for British high society.

The Department Store Revolutionizes the Retail Trade

Department stores such as Hermann Tietz in Berlin, Germany, also operated a mail-order business, selling not only ready-to-wear clothing but also other goods — Hermann Tietz, department store catalog, Spring 1906

Department stores such as Hermann Tietz in Berlin, Germany, also operated a mail-order business, selling not only ready-to-wear clothing but also other goods — Hermann Tietz, department store catalog, Spring 1906

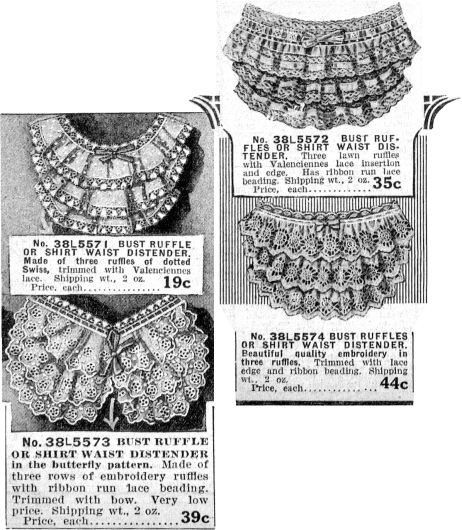

Bust ruffles of three-ply lace for furnishing and enlarging the female bosom, worn under the dress — Sears, Roebuck & Co., Spring/Summer 1913, p. 244

Bust ruffles of three-ply lace for furnishing and enlarging the female bosom, worn under the dress — Sears, Roebuck & Co., Spring/Summer 1913, p. 244

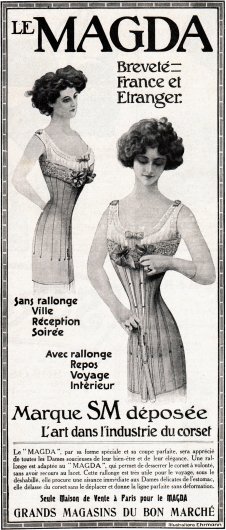

Exaggerated illustration of Magda corsets sold exclusively at the Bon Marché department store in Paris — Femina no. 233, 1910. Illustration: Ehrmann.

Exaggerated illustration of Magda corsets sold exclusively at the Bon Marché department store in Paris — Femina no. 233, 1910. Illustration: Ehrmann.

Among the Parisian department stores, the Bon Marché was the most successful of its time. Founded in 1838, the entrepreneur Aristide Boucicaut revolutionized the world of retail trade from 1852 onwards.6 His department store united under one roof for the first time a huge assortment of goods, which, by purchasing large quantities of goods and thanks to a high turnover rate, could offer all products at affordable prices. Boucicaut also turned the current price policy upside down. Instead of selling the goods at the highest possible prices, he offered everything at the lowest possible prices in order to achieve a higher profit through increased sales and despite a lower margin. Completely new were the services that Bon Marché offered its customers, such as the possibility of exchanging goods or returning goods with a refund, ordering by catalogue or free delivery of the goods to their home. The customers could take the goods in their hands and convince themselves of the quality of the goods. He also developed completely new methods of marketing in order to maintain customer interest and attract new customers.

In the following decades the Bon Marché became the model for other department stores in Paris such as Au Printemps, La Samaritaine and the Lafayette Gallery. The principle was quickly copied in other countries as well. Large department stores such as Whiteleys, Selfridges and Harrods in Great Britain, Wertheim, Karstadt, Hermann Tietz and the Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe) in the German Reich or Macy's and Woolworth in the USA followed the French model or interpreted it in their own way. By the end of the century, true cathedrals of consumption had been created in many major European cities, which, behind their historicising facades, housed modern steel skeleton constructions with magnificent interiors, thus making the act of buying a new and special experience.

Especially for middle-class women, the first spaces were created here, which freed them from their hitherto purely domestic existence and offered them public space for the first time through the lure of consumption. The department store advanced to a "paradise for ladies" 7 in such a way that the supposedly weak sex also tempted vice. Thus the phenomenon of kleptomania was declared by the still young psychiatry to be an almost exclusively female clinical picture.8

The Rise of the Mail Order Business in the USA

Front page of a 149-page New York mail order catalog from 1909 — National Cloak & Suit Co., Fall/Winter 1909-10. Illustration: Howard Chandler Christy (1872-1952)

Front page of a 149-page New York mail order catalog from 1909 — National Cloak & Suit Co., Fall/Winter 1909-10. Illustration: Howard Chandler Christy (1872-1952)

Two title pages of the German magazine Elegante Welt, which was published weekly from 1912 by Dr. Eysler & Co. GmbH - Elegante Welt no. 46, 1913 and Easter-issue no. 14, 1914. Illustrations: unsigned/unknown

Two title pages of the German magazine Elegante Welt, which was published weekly from 1912 by Dr. Eysler & Co. GmbH - Elegante Welt no. 46, 1913 and Easter-issue no. 14, 1914. Illustrations: unsigned/unknown

After the Civil War (1861-1865) and the subsequent Reconstruction, the United States of America experienced an era of unimagined economic upswing, which was only briefly interrupted by the stock market crash of 1873. Later, the period from 1875 to 1914 was called the Gilded Age. While industry and trade boomed and developed mainly in the urban centres on the east coast, most of the country was still predominantly agricultural and sparsely populated.

Far away from larger settlements, many farmers were dependent on the limited range of goods offered by local retailers, who exploited their monopoly-like position by charging high prices. With the idea of selling goods directly to the rural population via catalogue without an intermediary, Aron Montgomery Ward founded the first mail order company in the USA in Chicago in 1872. The first catalogue consisted of a single page. But the success was so enormous that within a few years until 1883 the catalogue grew to 240 pages with 10,000 articles. Although Montgomery Ward mainly sold clothing and textiles through the catalogue, the range of goods also included articles for daily use, household goods, furniture, tools, farm equipment and agricultural machinery.

In the late 1880s, other pure mail order companies such as the National Cloak and Suit Co. (1888), Bellas Hess and Co. (1888), Chicago Mail Order Co. (1889) and Philipsborn's (1890). In addition, many smaller local department stores, as in Europe, also began to enter the mail order business to expand their sales opportunities. But the biggest competitor for Montgomery Ward was established by Richard Warren Sears. From 1886 Richard Sears began to build up a flourishing watch mail order business. Sears published his first catalogue in 1888. With the arrival of the partner Alvah Roebuck in 1893, the company was renamed Sears, Roebuck and Co. The range of goods offered by the mail order company was rapidly expanded year after year. By the turn of the century Sears had become the largest mail order company in the USA with millions of customers and a catalogue that united an entire department store on over 1,000 catalogue pages.9 By the First World War, a large number of smaller and larger mail-order companies had established themselves, whose catalogues enabled the whole family to buy inexpensive clothing from the comfort of their own homes. The mail order business had become a firm institution in American society and a significant economic factor in the USA.

Civil Morals and Cosmetics

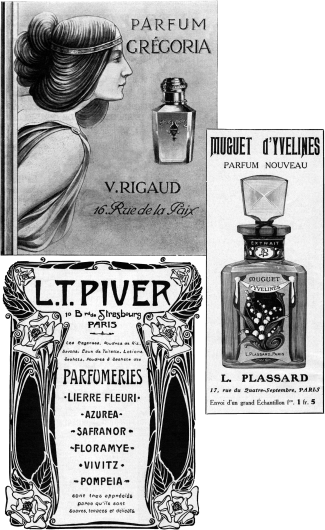

Advertisements for fragrances by Parisian perfumers V. Rigaud, L. Plassard and L.T. Piver, showing precious flacons or Art Nouveau ornaments — Collage from Femina no. 232, 233 & 235, 1910. Illustrations: unsigned/unknown

Advertisements for fragrances by Parisian perfumers V. Rigaud, L. Plassard and L.T. Piver, showing precious flacons or Art Nouveau ornaments — Collage from Femina no. 232, 233 & 235, 1910. Illustrations: unsigned/unknown

The ideal of the Belle Époque woman: fine angelic features, long flowing hair and natural beauty adorned only by noble jewelry — Collage from Elegante Welt no. 42 & 46, 1913. Photos: Neame (center), Técla Salon, Berlin, Germany

The ideal of the Belle Époque woman: fine angelic features, long flowing hair and natural beauty adorned only by noble jewelry — Collage from Elegante Welt no. 42 & 46, 1913. Photos: Neame (center), Técla Salon, Berlin, Germany

Natural beauty was the ideal of the 19th century and early 20th century. The use of colored cosmetics to make up the face was frowned upon and seemed disreputable. According to Annelie Ramsbrock, this general rejection of decorative cosmetics developed with the slowly emerging bourgeoisie of the late 18th century, who felt obliged to the values of the Enlightenment.10 Naturalness was associated with sincerity and trustworthiness, elevated to a virtue and, in addition, brought together with ideas of health and purity. In contrast, the painted noble ladies of the court aristocracy stood for intrigue and hypocrisy, hiding their faces with make-up as if behind a mask. The bourgeoisie of the 19th century understood itself thus also as a counter-draft to the courtly society of the absolutist Ancien Régime, which was considered as vicious.11

Besides morality, education was another virtue of the bourgeoisie. An educated woman - by which, however, by no means a scientific or even political education was meant - should, according to common opinion, not devote herself to superficial embellishment, but to inner cultivation and maturity. The more a woman devotes herself to outward vanity, the more she wants to distract herself from her inadequate nature and limited mind, according to popular opinion. Moreover, make-up also received religious criticism, since it corrected and consequently criticized the work of God and encouraged sin.12 Consequently, "women who appear natural [...] were said to have a morally impeccable nature, while an artificial-looking appearance [...] was considered an expression of outrage."13 Thus it should come as no surprise that make-up was often associated with depravity, prostitution and prostitution and was at best tolerated by theatre actresses.

The beauty guidebooks that appeared in a large number in the course of the 19th century propagated this natural ideal of beauty and criticized make-up, although they also passed on instructions for the domestic production of cosmetics and their use. The moral and religious concerns were accompanied by health reservations. Up to the end of the 19th century toxic substances like lead white, mercury and cinnabar were used for the production of cosmetics.14 With the increasing scientificization of chemistry and pharmacy, however, alternative ingredients and colours could be produced artificially. In 1879 the former singer Ludwig Leichner brought stage make-up onto the market, which was free of lead paint, and was subsequently distributed internationally.15 Also the French-born perfumer Èugene Rimmel started at the same time in London with the distribution of mascara which is harmless to health.16

Fashion of the Belle Époque until 1914

Front page of the French magazine Les Modes with Art Nouveau ornament and a hat creation by Suzanne Talbot worn by Mlle. Jeanne Saulier - Les Modes no. 88, April 1908. Photo: Paul Boyer (1861-1952)

Front page of the French magazine Les Modes with Art Nouveau ornament and a hat creation by Suzanne Talbot worn by Mlle. Jeanne Saulier - Les Modes no. 88, April 1908. Photo: Paul Boyer (1861-1952)

Two street costumes, each in two pieces, of blue panama and darker satin, and of a light striped summer fabric of choice and seams of pongee silk — The Delineator, March 1909.

Two street costumes, each in two pieces, of blue panama and darker satin, and of a light striped summer fabric of choice and seams of pongee silk — The Delineator, March 1909.

Women's fashion at the turn of the century was characterized by floor-length but high-necked dresses, whose lavish and pompous presentation and multi-layered undergarments and petticoats significantly restricted and influenced the movement of the wearer. Even more than the dresses, the corset formed the desired tight waist and straight posture of the lady. From 1895 the S-curve or hourglass silhouette came into fashion. While the abdomen was pressed backwards and laced away by the Sans-Ventre corset (French: "without stomach"), the chest was forced forward. The low neckline of the corset and the lack of shaping and modelling of the breasts led to the so-called monobosom effect. Showing leg and skin was unthinkable for decent women - just like for men. Especially the swimwear was characterized by cloaking prudery. Sunbathing and the tan associated with it were frowned upon, since the tan was considered a sign of the lower layers whose skin was exposed to the sun during work.

In the USA, the ideal of the woman on the threshold of the 20th century was based on the Gibson Girl - named after the illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. This ideal image of the young woman was characterized by a tall, athletically slender figure, a feminine bust and hips and a narrow waist. Just like in Europe, a sprawling head of hair was the symbol par excellence of female beauty and was considered the crowning glory of femininity. Hairstyles were often decorated and enriched with jewellery, feathers and combs. Human hair pieces and also discreetly worked in padding gave the hairstyle even more volume.17 Women who opposed this ideal and wore their hair short were considered social outsiders.

Reform Fashion, Hobble Skirt and Oriental Wave

A light blouse - often made of lace - with a stand-up collar was worn under the dress. Fine gloves, small handbags with tassels and small hats with graceful feathers or other trimmings were fashionable — The Delineator, November 1914

A light blouse - often made of lace - with a stand-up collar was worn under the dress. Fine gloves, small handbags with tassels and small hats with graceful feathers or other trimmings were fashionable — The Delineator, November 1914

The tunic dress defined the fashion in 1914. One wore a wider flared overskirt over the tight hobble skirt - the beginning of the war crinoline. The waist was emphasized by gathering or wrapping effects — The Delineator, November 1914

The tunic dress defined the fashion in 1914. One wore a wider flared overskirt over the tight hobble skirt - the beginning of the war crinoline. The waist was emphasized by gathering or wrapping effects — The Delineator, November 1914

At the beginning of the 20th century, women's rights activists made their first attempt to simplify fashion with the reformist fashion, which was intended to give women more freedom of movement and was above all directed against the fashion dictates of the S-curve. However, these unadorned and, on average, very clumsy dresses were rejected by the ladies of society and at best smiled at. Only in intellectual circles could these dresses assert themselves. It was not until 1908 that a new fashion line began to establish itself, which dispensed with the unhealthy S-curve and completely pushed it out of fashion in the following years. The corset itself was made of lace, brocade, coutil (robust cotton fabric) and whalebone. The whalebone, also known as whalebone, was increasingly replaced by spiral-shaped, flat steel wires. The corset itself remained an indispensable part of women's wardrobe until the First World War and far beyond.

In the years after the disappearance of the S-curve the skirts became tighter and tighter. Fashion was oriented towards the slender Empire fashion - or Directoire style - of the early 19th century with very high waists. From 1910 onwards, such tight skirts appeared, which restricted walking so much that the wearer was only able to do short triple steps. This so-called hobble skirt remained an integral part of fashion until 1914, although many of these skirts had slits or hidden pleats that made walking easier. Besides, the hems of the skirts became shorter for the first time; the slit skirts even revealed the ankles here and there. At the end of 1913, the first crinolines appeared in the form of "cerclette hoops"18, small delicate over-skirts, which were to develop into the war crinoline in the following years. Paul Poiret was the authoritative creator of this new silhouette and before the First World War one of the most influential fashion designers of his time.19 His exotic, oriental-influenced creations with hobble skirt and crinoline determined the fashion of spring 1914 - the eve of the First World War.

Footnotes

1 Alsen, Ola, Das Kennzeichen des neuesten abendlichen Modestils ist Weiblichkeit, in: Elegante Welt, no. 21 (18), October 14, 1929, pp. 30-31 and 58, here p. 30.

2 Carter, Erica, Frauen und Oeffentlichkeit des Konsums, in: Heinz-Gerhard Haupt, Claudius Torp (ed.), Die Konsumgesellschaft in Deutschland. Ein Handbuch, Frankfurt/Main 2009, pp. 154-171, here p. 154.

3 Ibid., pp. 157-158.

4 Worsley, Harriet, Fashion. 100 Jahre Mode, Koenigswinter 2004, p. 10.

5 Brief outline of John Redfern's life and work: http://headtotoefashionart.com/john-redfern-1853-1929 [last accessed: September 21, 2014].

6 In this context, the ARTE documentary by Sally Aitken and Christine Le Goff from 2011 is very interesting: "Wishes come true — the creation of the department store". Available under the following link (in German): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPvf_bIMEjQ&list=PL11AA0E937E529244 [last accessed: September 21, 2014].

7 In his novel "Au Bonheur des Dames", French author Émile Zola described the social and societal changes that department stores set in motion in Paris during the Second Empire. Zola had previously researched the Bon Marché for his novel. Zola, Émile, Au Bonheur des Dames, Paris 1884.

8 Carter, Women, pp. 159-160, as note 2.

9 Sorensen, Lorin, Sears, Roebuck and Co., 100th Anniversary 1886-1986, St. Helena (California) 1985, pp. 6-10.

10 Ramsbrock, Annelie, Korrigierte Koerper. Eine Geschichte kuenstlicher Schoenheit in der Moderne, Goettingen 2011, pp. 85-90.

11 Ibid., p. 89.

12 Ibid., pp. 32-40.

13 Ibid., pp. 88-89.

14 Ibid., p. 63.

15 Lohse-Jasper, Renate, Die Farben der Schoenheit. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Schminkkunst, Hildesheim 2000, pp. 91-93.

16 Jones, Geoffrey, Beauty Imagined. A History of the Global Beauty Industry, Oxford 2010, pp. 18-19.

17 Worsley, Fashion, 2004, p. 41, as note 4; Kniebiehler, Yvonne, Leib und Seele, in: Geneviève Fraisse, Michelle Perrot (ed.), Geschichte der Frauen (vol. 4), 19. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt/Main 1994, pp. 373-416, here p. 375.

18 Marion, Die Krinoline ist wieder da!, in: Elegante Welt, no. 49 (2), December 3, 1913, pp. 17-18.

19 Worsley, Fashion, 2004, p. 11, as note 4.